AI: Artificial Inventor? The battle for AI's patent rights

The English Court of Appeal has upheld the decision made by the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) to reject two patents which listed the inventor as DABUS, an artificial intelligence (AI) program.

DABUS’s creator, Dr Stephen Thaler, filed two patent applications back in 2018, one for a type of food container (Pub. Number: 2592777) and one for a flashing light (Pub. Number: 2575131), both ideas having been invented using the DABUS program.

In the forms filed, Dr Thaler listed ‘DABUS’ in the section for the name of the inventor and in the box requiring him to indicate his right to be granted the patent, he wrote “by ownership of the creativity machine DABUS”, going on to explain that the machine had generated the inventions.

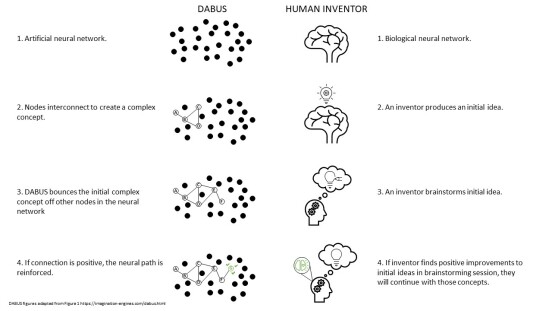

DABUS works by using large artificial ‘neural net’ systems (similar to biological neurons in a brain). These nets are constantly combining and detaching due to the controlled chaos that is written into the code, i.e. consistently making pathways between each other and then breaking them. If a node interconnects with multiple other nodes it creates a net which represents a complex concept, i.e. an inventors ‘eureka moment’ where an initial idea is formed.

The algorithm then ‘bounces’ that initial complex concept net off other chains stored in the neural network. With each connection it works out the consequences of adding these extra nodes to the initial idea and whether it would have a positive, or negative effect on the invention as a whole. If the connection is a positive one the programme reinforces that pathway, whilst the opposite is true for a negative effect, similar to an inventor brainstorming their invention against their own memories or ‘stored thoughts’.

In August 2019, the UKIPO responded to the application filed by Dr Thaler, stating that section 13(2) of the Patents Act 1977 (UK) says that the applicant must identify “the person or persons whom he believes to be the inventor or inventors”.

Disagreeing with the UKIPO’s decision, Dr Thaler took the case to the High Court – where he lost – and on to The Court of Appeals which agreed with the UKIPOs original ruling by a 2-to-1 majority. "Only a person can have rights. A machine cannot," wrote Lady Justice Elisabeth Laing. Lord Justice Arnold agreed with this decision, writing "In my judgement it is clear that, upon a systematic interpretation of the 1977 Act, only a person can be an 'inventor'." This contradicts the decision by the Australian and South African courts earlier this year, but in line with the US court’s decision.

The last few years have shown that AI techniques are capable of enabling partial automation of the inventive step, but they still require a human input to specify instructions that henceforth determines the output of the program. As long as computers are limited by such instructions they can therefore only be seen as a tool which has aided the inventive step in the same way that microorganisms have not been considered inventors despite being used in R&D of biotechnological inventions.

Perhaps, as AI technology continues to grow in the future, the current criteria for inventorship may change to consider the role that machines can play in the inventive process, but for now Dr Thaler (and DABUS) have 28 days from the decision to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Lauren Mills, PhD (Biochem) student and Intern for ip21 Ltd

For advice on any aspect of patent strategy please get in touch with our team of experienced patent attorneys - Contact us